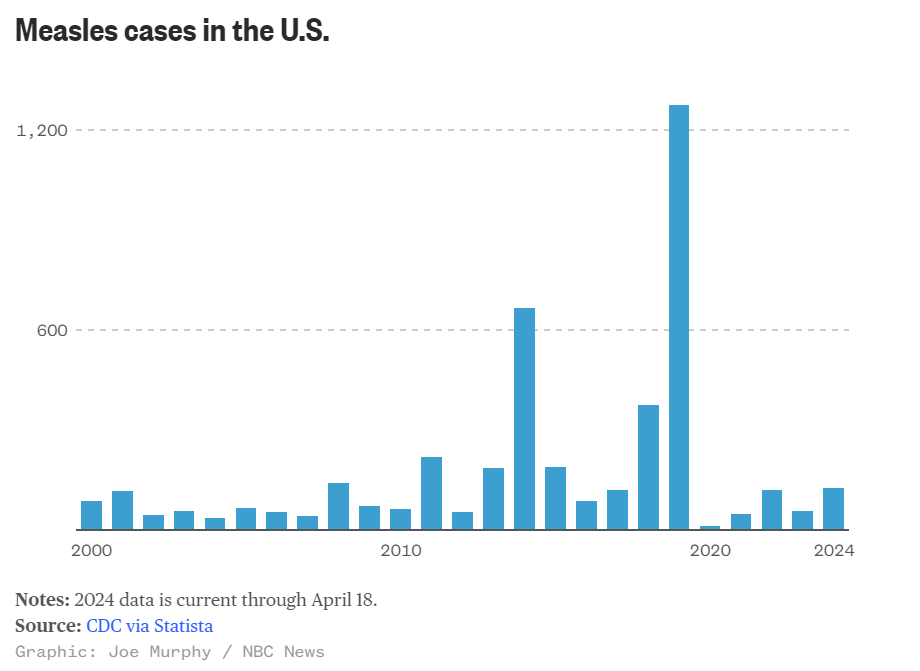

Several outbreaks, including one in Chicago, led to an early spike in measles cases this year. A chart shows how the case count compares to past years

(NBCNews, Aria Bendix and Joe Murphy) — This year’s measles case total is now the highest of the last five years. The United States has seen 125 cases across 17 states as — its largest annual tally since 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

From January to March, the U.S. recorded around 30% of the total cases seen since the beginning of 2020, according to a CDC report released earlier this month.

The authors warned that the rapid increase in cases “represents a renewed threat to elimination.”

Most cases reported this year were linked to international travel, and the majority were among people who had not received a measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine or whose vaccination status was unknown.

Two doses of the vaccine are 97% effective, but the CDC said in an advisory to health care providers last month that “pockets of low [vaccination] coverage leave some communities at higher risk for outbreaks.”

This year’s early spike in measles cases was driven in part by outbreaks centered in a migrant shelter in Chicago, an elementary school in southeast Florida and a children’s hospital and a day care center in Philadelphia.

Chicago continues to confront its outbreak. As of Monday, its case count had reached 63, with the most recent recorded last week. More than half of the cases were among children under age 5.

Though disease experts have expressed concern about the early rise in cases, the U.S. isn’t close to its total from 2019, when the country nearly lost its measles elimination status. Most of the 1,249 cases that year were associated with outbreaks in Orthodox Jewish communities in New York.

Measles is highly contagious: An infected person can spread it to up to 90% of people close to them if those contacts aren’t immune. Thanks to widespread vaccination, measles was eliminated in the U.S. in 2000 — meaning that it’s no longer constantly present, though there are still occasional outbreaks.

Most people who get measles now are unvaccinated. Children in the U.S. are meant to get their first vaccine dose between 12 and 15 months and their second between 4 and 6 years old.

However, vaccination rates have fallen in the last few years. For nearly a decade, 95% of U.S. kindergartners had received two doses of the MMR vaccine. That rate fell to 94% in the 2020–21 year, then to 93% in the 2022–23 school year.

Measles symptoms usually start with a high fever, cough, conjunctivitis (pink eye) and runny nose. Two to three days later, people may notice tiny white spots in their mouth. On days three to five of symptoms, a blotchy rash often forms at the hairline before spreading to the rest of the body.

Some people may develop severe complications from measles, including pneumonia, swelling of the brain or a secondary bacterial infection. Before measles vaccines became available in 1963, around 48,000 people were hospitalized and 400 to 500 people died of the disease each year in the U.S.

Today, 1 in 5 unvaccinated people who get measles are hospitalized, and roughly 1 to 3 out of every 1,000 children with measles die from respiratory and neurological complications, according to the CDC.