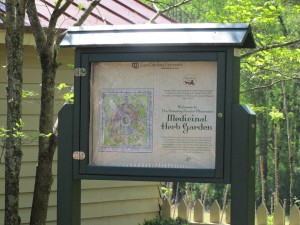

Thanks to the generosity of longtime North Carolina Medical Society (NCMS) member Gloria Graham, MD, 2015 NC Doctor of the Year, the Country Doctor Museum in Bailey has a new information kiosk in its popular medicinal garden. Dr. Graham donated part of her $5,000 NC Doctor of the Year award to the museum, which she helped found.

Thanks to the generosity of longtime North Carolina Medical Society (NCMS) member Gloria Graham, MD, 2015 NC Doctor of the Year, the Country Doctor Museum in Bailey has a new information kiosk in its popular medicinal garden. Dr. Graham donated part of her $5,000 NC Doctor of the Year award to the museum, which she helped found.

“It’s something we’ve been wanting for some time,” said Anne Anderson, the museum’s curator. The kiosk will “help people enjoy the garden when we’re not here to explain it to them.”

The garden, which was dedicated in 1971 and features an assortment of carefully labeled medicinal plants, is open even when the museum buildings on the site are closed. Garden clubs and others who enjoy the serene surroundings frequent the garden, and the kiosk will offer information on the plants and seasonal features of note.

On Saturday, April 30, at 1 p.m., Dr. Graham officially will unveil this latest addition as part of the museum’s Springfest and Plant Sale. Everyone is invited to the daylong festivities, which include free tours of the museum and garden, herbal tea tastings as well as homemade baskets and a wide variety of plants and natural products available for purchase. For more information on Springfest, visit the Country Doctor Museum website or call 252-235-4165.

Dr. Graham along with her good friend and colleague Josephine Newell, MD, the NCMS’ first woman president, were instrumental in founding the Country Doctor Museum in 1967 as a lasting tribute to their physician ancestors. Dr. Newell was the seventh in a direct line of country doctors, and lived in the house next door to the current museum buildings for many years. Dr. Graham’s father, James Meigs Flippin, MD, was a country doctor in Pilot Mountain, NC, practicing for 77 years. Several artifacts from his office are displayed in the museum including his double roll top desk.

Dr. Graham along with her good friend and colleague Josephine Newell, MD, the NCMS’ first woman president, were instrumental in founding the Country Doctor Museum in 1967 as a lasting tribute to their physician ancestors. Dr. Newell was the seventh in a direct line of country doctors, and lived in the house next door to the current museum buildings for many years. Dr. Graham’s father, James Meigs Flippin, MD, was a country doctor in Pilot Mountain, NC, practicing for 77 years. Several artifacts from his office are displayed in the museum including his double roll top desk.

Dr. Graham remembers her father’s practice well since it was in their home, as was often the case for rural physicians in the late 19th and early- to mid-20th centuries, the period covered by the museum.

“We’d have people knocking at the door and coming into the office at all times — day and night. And I went on baby cases, sometimes two or three nights a week,” Dr. Graham recalled in a 2011 article in Dermatology Times. “He delivered all the babies in that area until he was about 92 years old. He delivered the last one at 94. Nobody else could come, and he went in and delivered it on the living room couch.”

The Country Doctor Museum explores what life was like for both the doctor and the patient. The Carriage House focuses on how doctors got to their patients – horse and buggy or, later, Ford Model T’s – with the actual vehicles used by country doctors on display. Among the more than 5,000 medical artifacts featured in the museum building, which is made up of two historic country doctor offices relocated to the site, are the tools, formularies, patient ledgers, apothecary items for mixing and rolling pills, amputation kits dating back to the Civil War as well as blood-letting instruments and live medicinal leeches to help illustrate advances in medical science.

“Country doctors were really connected and involved in the life of the community. They had leadership roles,” Anderson said. They would care for everyone in a community without regard to whether the patient could pay. The patient ledger on display notes patients who paid for their care with corn, ham, peaches or work. “It was often a barter system,” Anderson said. “There was always that balance between wanting to help and collecting enough money. They didn’t become wealthy, but they had a comfortable life. The community looked out for them.”

As an integral part of the community, the physician often didn’t even need to take a health history since they knew the families so well.

While there are many differences between rural physicians of yesterday and those of today, Anderson pointed out there seems to be a harkening back to some of the old ways. For instance, taking narrative medical histories has returned in certain practices, employing a scribe so physicians have more face time with their patients while still fulfilling electronic medical record requirements, even models of care that center on making house calls.

The quality that transcends time and place, Anderson believes, is what she calls the “spirit of the country doctor.” That spirit means, first and foremost, compassion and caring for the patient, a quality that lives on in the practice of medicine today.

The Country Doctor Museum is governed by the Eastern Carolina University Medical Foundation and managed as part of its Health Science Library. Monetary donations may be made directly to the Country Doctor Museum. To donate an artifact consult the guide to donating artifacts here.